Beekeeping used to be simple according to Denny Redman. “It used to be a lot easier to keep bees,” Redman said. “Now it’s more of a challenge.” He has been a beekeeper since about 1972, before Colony Collapse Disorder began confounding beekeepers and researchers. Before the blood-sucking varroa mite began crippling colonies. Before mass die offs became part of doing business. “It was just like a pleasure,” he said. “Now more people are serious about it. There’s a lot of concern about what’s happening.”

As beekeepers know all too well, the parasitic varroa mite poses the biggest threat to colony health across North America. They weaken the colony, rendering it susceptible to numerous other ailments and affecting the bees’ ability to forage and care for the brood.

This is why Redman decided to participate in research about mites.

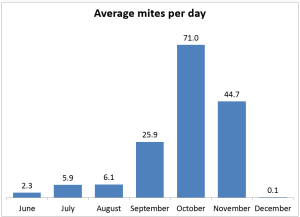

Beekeeper and entomologist Danny Najera has undertaken an effort to gather information about mites and he needs beekeepers’ help. Najera uses a nonlethal method to gather samples from area colonies before counting the mites in the samples under a microscope. With some help from students, he recently counted nearly 11,500 mites taken from eight different colonies, including Redman’s samples were collected between June and December 2013.

“We are not sure yet exactly what these mite drops mean,” Najera said. “This is another confounding part of the data collection. Do healthy mites drop? Do sick mites drop? Do other bees pick off mites? What percentage of mites drop relative to how many mites are present?”

There was an average of more than 141 mites per sample. The highest counts occurred in October, when there is a natural decrease in colony size, giving mites the upper hand.

“This is a time period when the amount of food available to a honeybee colony drops and you still have lots of bees, so bees start to get a little stressed, which makes them more susceptible,” he said. “As the number of honeybees drops, the ratio of mites to honeybees increases drastically and can wear down a colony before going into winter.”

Najera said far more data are needed to draw any meaningful conclusions. “There are many different ways that people keep bees,” he said. “And so many different areas. Near the water, away from the water, near parks that are sprayed with pesticides. The number of variables is just so high.”

“The only real solution is the long-term study,” he said.

Fearful of how information about their colonies may reflect on them, many beekeepers are hesitant to participate, even though they stand to benefit the most from such information.

That is why Najera keeps personal identifying information confidential. He takes privacy very seriously.

Many beekeepers also want answers right away, but Najera urges them to think about the long-term value of the research.

“This will be ongoing,” he said. “We’re establishing baselines. There are no baselines for this part of the world. If it matches with other parts of the country, great, but if not, we need to know that.”

Other sampling techniques, such as an alcohol wash, involve killing hundreds of bees, something many backyard beekeepers are unwilling to do. The sampling method used in Najera’s research allows mites to be collected on a tray beneath the colony, without killing any bees.

Using this method, beekeepers can sample 30 or 40 times per year, at any time of the year, something that would not be possible with lethal methods.

Research has been conducted in other parts of the country using a similar non-lethal method. Najera believes we need to gather data in such a way for comparison.

In the future he plans to collect samples by having beekeepers take photographs of the tray, which he hopes will make it easier to both submit and analyze otherwise messy samples.

Peter Barton, another beekeeper who participated, said collecting the samples was not difficult and urged other beekeepers to get involved.

“I would certainly encourage people to do it,” he said. “It’s a learning experience.”

Najera will also analyze future samples for pollen types and other organisms that he observed in the first round of data collection.

Expressing a sentiment shared with him by his PhD mentor, who himself was mentored by renowned ethologist Karl von Frisch, Najera said the research is critical, regardless of the results.

“The best scientific investigations produce useful outcomes, no matter what the results,” he said. “In this case, if our data matches previous data, we no longer need to kill bees to get the data. If not, then we’ve learned something new.”

Although beekeeping has become far more challenging, beekeepers like Redman carry on; welcoming any insight, they can into the plight of that which they love.

“I think bees are one of the most wonderful creatures on earth,” Redman said. “I love bees.”

Thanks to Chelsea Bannach for sharing this article.

| For more information on how to participate in the research, contact dnajera@greenriver.edu or call (785) 230 4521 |